Deep in the north country of Texas, Sharon Wilson — a fifth-generation Texan — and her son used to take her 1996 Chevy truck and drive into the pasture on clear nights. Out there, lying in the bed of her gold pickup truck, snacks in hand, they could see a million stars. That was before the fracking started. ….

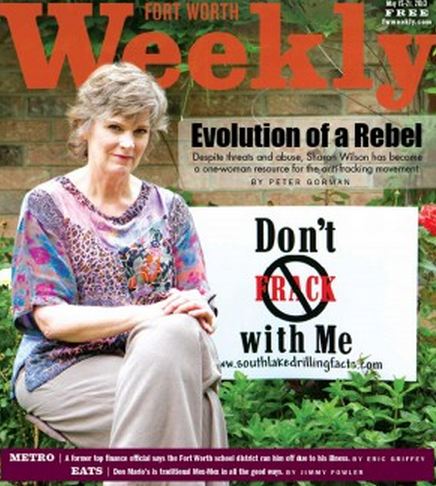

WORLD CRACKED OPEN: WHEN FRACKING CAME TO TOWN by Lana Cohen, Nov 26, 2019, whowhatwhy.org

Wilson, now a senior organizer at an environmental advocacy group, worked for 12 years as a data manager in the oil and gas industry.

“I left because I objected to their ethics,” she said. “They felt like if they thought of an idea, they were entitled to profit from it no matter who got hurt.”

Wilson had long dreamed of a life in the country. Although she grew up in Fort Worth, Texas, she spent as much time as possible outdoors. As a child, when she wasn’t in school she was at her grandparents — riding horses and “running wild.”

“I wanted my kids to grow up that way,” said Wilson. “Feeling safe and free.” In the mid-90s, with her infant son in tow, she bought 42 acres in Wise County, Texas, and set out to turn her fantasy into reality.

“When I first bought my property, it was a dream come true, she told WhoWhatWhy. “The air was beautiful and clean when we first moved out there and the sky was this gorgeous color of blue. I mean blue, not this washed out blue you see in the cities, but this vivid, electric blue.”

The dense woods on Wilson’s property filled the land with more splashes of color: magenta berries, flowering plum trees, and dazzling green grass. The woods were not only home to Wilson, but to scores of deer and countless birds who found freedom and safety, as Wilson thought she had, in this sparsely populated area in Texas near the Oklahoma border.

Across her property was an idyllic pond and gully, which fed right into a Bermudagrass pasture where her horses fed. Wilson would ride her horse out her gate and into the Lyndon B. Johnson (LBJ) national grassland, finding herself in spots where she could no longer see or feel the presence of man — no fences, no houses, no roads. “It was paradise,” she said.

What she didn’t realize four decades ago was that she was establishing her home next door to one of the nation’s first and most widespread experiments in fracking — cracking open the Barnett Shale.

Unknown to her, George P. Mitchell, the father of fracking, was well on his way to completing a more than decade-long experiment and unleashing an energy boom across the United States. He was figuring out how to produce oil and shale gas commercially right in her front yard.

Being neighbors with one of the first big fracking operations would turn Wilson, now a senior organizer at Earthworks, into a scholar of natural gas extraction, a community organizer, and, ultimately, an environmental organizer. Instead of retreating into a rural paradise, she would find herself going toe-to-toe with vested corporate interests, powerful lawmakers, neighbors, and community members who she believes were focused solely on their pocketbooks.

She would be forced to grapple with uncomfortable trade-offs. “I know people make money on fracking and I know people need money to live,” conceded Wilson. “But they can have jobs that are safer, cleaner, and longer-term in renewables.” At the end of the day, money isn’t going to solve the environmental and health problems caused by fracking and money isn’t going to bring back rural paradise, explained Wilson.

…

According to a study published in the Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Global Public Health, fracking has been linked to increased heart problems, early births, high-risk pregnancy, certain types of cancer, asthma, migraine headaches, skin disorders, fatigue, and nasal and sinus symptoms.

In Wise County, Wilson watched as fracking put an end to her quiet. country lifestyle. “There was diesel from the rigs and soot from the flaring and horrible emissions. Eventually, my air turned brown and my water turned black.”

“The polluted air was the worst,” said Wilson. “Because you can get clean water somewhere, it’s not ideal, but you can get it. You can’t get air.”

This story is not unique. Wilson said she has corresponded with hundreds of people with similar stories, all having their lifestyles eroded by fracking.

“You have this deep connection and caring for each other because you have gone through something traumatic. Because I’ve lived through it, I can help other people,” said Wilson. “I know exactly what it feels like to have your American dream, and then realize that your paradigm of America was false.”

Photo credit: Courtesy of Sharon Wilson

… One spring morning, Wilson went outside for a breath of fresh air. The seasons were changing and the grass was shooting up out of the earth. She walked to her favorite spot to enjoy the vista of grassy landscape, a hilltop that looked down on a bright green meadow below. But when she looked down, there was nothing there. Nothing but a big dead spot where a waste hauler had dumped his load. “There were many moments that came together to break the camel’s back,” said Wilson. “That was one of the moments.”

With the nearby fracking encroaching on her property and her life, Wilson decided to take matters into her own hands. She started documenting everything she was seeing — writing a blog, taking pictures. She wrote letters to the local newspaper, and sent essays to be published as op-eds. “At the time, I believed they could and would do better.”

The fracking operation had put up lights everywhere, creating a brilliant, twenty-four hour daytime scene. Wilson and her son’s stargazing days were gone. There was no more driving out into the pasture together or staring up at the endless night sky — at the Milky Way and Big Dipper, learning the constellations together. “You can’t see any stars out there anymore.”

Wilson reached a point where she had to make a choice — invest in fixing up her land and live here with a young child or move into town where he wouldn’t be exposed to drilling, fracking, and pollution. Seeing that the lifestyle she had wanted was no longer possible in Wise County, she chose the latter.

…

In 2010, when all was said and done, she chose the city of Denton, Texas, about an hour north of Dallas, to be their new home. But by then, fracking was on the rise.

“There was just as much drilling, just as much pollution,” said Wilson. …

… The Texas Commission of Environmental Quality found airborne benzene near Barnett Shale wells at levels of 500 to 1,000 parts per billion (ppb). The EPA has set the permissible outdoor air level at 5 parts per billion, according to SourceWatch.

… Finding many of the problems in Denton that she thought she had left behind, Wilson again sprang into action. “We had a campaign,” said Wilson. “An incredible campaign.” As part of the scrappy team Denton Drilling Awareness Group, Wilson canvassed throughout the city. “We showed up everywhere. If they had an event at the dog park, we were there. At the farmers market, we were there. Whatever event they had, we were there.”

In November 2014, fracking went on the ballot. “We banned fracking with 60 percent of the vote in a predominantly Republican county, in a predominantly Republican state.”

Less than a year later, then-Gov. Greg Abbott (R) signed House Bill 40, which gives the state exclusive jurisdiction over oil and gas operations and prohibits local municipalities from creating ordinances that ban, limit, or regulate oil and gas operation in favor of development of oil and gas resources and economic prosperity.

“We have tried to live with fracking,” said Wilson. “We tried, but we can’t.”

Refer also to:

2013: Sharon (Tx) Wilson: A Texas Rebel’s Fight for Her Land