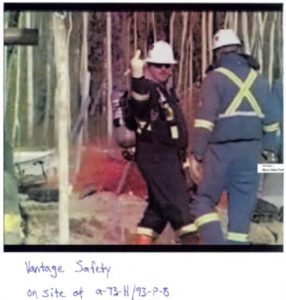

This is what the frac’ers really think of us, our loved ones, home, health and communities; Encana contractors give press the finger responding to the sabotage:

Chapter 10 Loud Bangs and Quiet Canadians: An Analysis of Oil Patch Sabotage in British Columbia, Canada by Chris Arsenault, 2010, in Critical Environmental Security: Rethinking the Links Between Natural Resources and Political Violence Edited by Matthew A. Schnurr and Larry A. Swatuk, Centre for Foreign Policy Studies Dalhousie University

Stating a common view among long-term residents of BC’s northeast, Eric Kuenzl, a landowner from Tomslake who met with EnCana in June 2008 about concerns such as road traffic, noise and possible health effects from sour gas told a local newspaper: “I feel like the company [EnCana] is the bully on the block, and I’m the kid who’s trying not to have my lunchbox stolen.” Kuenzl, whose family has lived on the same property since 1939, said he is ready to leave because he’s scared of the long-term health effects of flaring pollutants and hydrogen sulphide, or sour gas. As Canada becomes an “energy superpower,” in the words of Prime Minister Stephen Harper, debates about the nature of regulation and conflicts in the oil patch will only grow more intense.

This paper will analyse sabotage against EnCana in British Columbia in the context of broader conflicts between gas companies and other land users, specifically, farmers, rural residents and environmentalists. Social conflicts stemming from environmental grievances have become a major field of study for academics. Battles between farmers and oil companies are traditionally framed as conflicts stemming from property relations. This paper will argue that property relations, where individual owners control the above-ground area but not subsoil resources, are not the driving force inspiring conflict. Rather, the underlying cause of conflict in northeastern BC stems from captive regulatory agencies, regulators who favour petroleum companies and increased extraction at the expense of other land users. This capture arises from growing government dependence on petroleum revenues along with power imbalances between oil companies and other land users. The main reasons why regulations are flawed or improperly enforced, argues environmental law expert David Boyd, are “short term economic considerations such as profits, competitiveness and jobs.” In a commentary, the Canadian Association of Petroleum Producers concurs with the notion that pro-industry provincial regulatory regimes are a prime reason for the exponential increase in extraction.

…

EnCana’s comparative advantage in its North American holdings comes not from the resource itself, which is unconventional and harder to access than typical petroleum deposits, but from Canadian political stability. The desire to exploit stable deposits as fast as possible in BC is, ironically, creating instability

…

The threat of political instability is the main cause for aggressive state (250 highly trained officers sent to the region) and corporate (a one million dollar bounty) responses to sabotage in northeastern BC. “Capital is a coward and it runs away from risk,” notes the CEO TransCanada Corp, another major pipeline company.

…

The final section of the paper will use a case study from a well explosion at an EnCana facility to dispel the idea that oil capitalists, police and politicians are using aggressive measures against sabotage due to concern for public safety. To make its case, this study will utilize interviews and original research from communities where sabotage has taken place, a series of freedom of information requests to relevant government departments including the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP), the Department of Fisheries and Oceans and the Canadian Security Intelligence Services (CSIS), and a review ofsecondary literature.

…

Farmers, and other residents who have a connection to the land where petroleum extraction is happening, say rules governing extraction favour corporate land access above health, safety, the environment and basic dignity for other land users. In essence, petroleum companies have ‘captured’ government regulatory bureaucracies for their own benefit.

…

Since the BC government initiated a major overhaul of the province’s environmental regulations in 2002, if not before, both regulators are seen as captive. The DawsonChapter 10: Loud Bangs and Quiet Canadians Creek Daily News reports that many landowners “believe both of these groups are in the pocket of oil and gas companies and have little faith in their ability or desire to take their issues seriously.

…

After their 2001 election, the Liberals promised to double gas production by 2011. The year 2002 is arguably the most important single point for assessing when regulatory bodies in BC became captive to the interests of industry. The Campbell government amended the Oil and Gas Commission Act as part of a far-reaching energy strategy, placing the Oil and Gas Commission under the direct control of the Minister of Mines and Energy, the same body tasked with expanding the gas industry. This move eliminated notions of the OGC as a neutral regulator. The Liberals also changed the province’s Environmental Assessment Act “replacing one of the country’s most progressive provincial EA laws with one of the weakest” according to David Richard Boyd.

Some of these repercussions can be seen in the high number of spills, accidents and other problems. In its 2002/03 annual report, the Oil and Gas Commission states that compliance with regulations is “the responsibility of the oil and gas industry…. This can be achieved through the implementation of self-imposed guidelines.” Allowing industry to ‘self-impose’ is not a sensible way to enforce environmental laws. The Vancouver Sun obtained statistics from the commission indicating that when inspectors did check on gas operations, the vast majority were breaking the law.

…

At the height of the anti-EnCana sabotage campaign, the situation with compliance had not improved in many respcts. In a 11 February 2010 report, BC’s Auditor General found the Oil and Gas Commission was not making significant progress in cleaning up contaminated sites. “I had expected more progress because this is not our first audit dealing with contaminated sites in British Columbia,” said the Auditor General, referencing a 2002/03 report on provincial contaminated sites. “The oil and gas industry in B.C. has seen significant growth over the last decade, which has the benefit of increased revenues for the province, but also carries greater risks of contamination,” says the report. Among the report’s findings, companies are not doing enough to restore exhausted drilling sites, placing undue pressure on the province’s orphan well fund. The OGC downplayed the Auditor General’s concerns.

…

Upon becoming Chair of the Mediation and Arbitration Board (MAB) in 2007, Cheryl Vickers admitted that the board was “a mess” and had “no credibility.” … Vickers was not the first MAB official to criticize the organization. “From my experience in the past I do not believe that government really wants a Mediation and Arbitration Board to be a help to the landowners or anyone else that wants to bring a case before the board,” said former board member Thor Skafte in 2006. Gas companies were (and are) using the MAB to gain access to private land without disclosing the locations of wells and pipelines. Essentially, companies were filing arbitration orders before explaining their plans to farmers, leading Vickers to admit that the MAB was “all sort of ass backwards.”

…

Companies in BC can use what legal experts colloquially call ‘scorched earth’ tactics – i.e., marshalling superior financial resources to bankrupt your opponents and force them to concede defeat.

…

Since the sabotage campaign began in the fall of 2008, police, government officials and EnCana have claimed that protecting public safety is reason for a harsh state security response and a one million dollar bounty on the saboteur. “We take the bombings of our facilities very seriously. The safety of our workers and the people who live in the communities where we operate is of paramount importance. That’s why we are putting up this reward to help stop these bombings and end the threat that they pose to people in the Dawson Creek area,” said Encana spokesman Mike Graham. However, when recent history is scrutinized, these statements seem disingenuous. On 22 November 2009, an EnCana pipeline near Tomslake burst, releasing 30,000 cubic metres of toxic sour gas into the community. “This is a very serious event,” said Oil and Gas Commission spokesman Steve Simon. “This shouldn’t have happened.” In its assessment of the leak, the OGC reported a resident first smelled gas at 2:30 am. The company’s emergency shut-off valve failed. The first call came into 911 at 8:36 am, after a resident drove through a cloud of poison gas. The community self-organized an evacuation with a flurry of phone calls. EnCana didn’t tell residents about the danger until 10:16 am, several hours after the pipeline burst. The company didn’t stop the leak until 10:45 am. “Clearly, procedures were not followed,” EnCana Vice-President Mike McAllister told reporters at a Calgary press conference, where he issued an apology. No one was arrested or criminally charged as a result of the incident; in fact Encana did not even have to pay a fine. “This leak probably released thousands of times more gas than what has been released by the bombings,” said Tim Ewert, one of the dozens of people who had to evacuate themselves.

If safety was the over-riding concern, Encana would have had to do more than issue an apology. And while the ‘capitve’ OGC regulator did issue a thorough report and strong statements on the leak, there was no concerete action. This incident and the responses to it provide clear evidence that public safety is not the main factor motivating state responses to sabotage. Thus, it seems as though providing security for capital investment, partially as a means to bolster government petroleum revenues, is the over-riding public policy concern for the police, EnCana and the BC government. Unlike the seemingly intractible problem of property relations, these grievances can be dealt with primarily through legal changes. Thus captive regulators, not issues with property rigths are the main cause of confict and sabotage in northeastern BC. [Emphasis added]

Refer also to:

Encana Reaches Compensation Deal for Sour Gas Leak

$250,000.00 in community safety projects following Encana deadly sour gas leak