ERCB was EUB, is now AER

My ex lawyer, Murray Klippenstein, on the Board of the “regulator” of his profession – the Law Society of Ontario (LSO), quit abruptly via email on August 26, 2018, withheld my website for nearly a year, ignored my correspondence, withheld my trust funds a year, and to this day, continues to withhold my case files (contrary to the rules of his profession and his written promises to me in 2018 and 2019).

Cory Wanless, who started his career fresh out of school with my case, including representing me at the Supreme Court of Canada, could send me the case files he was working on, but has not, claiming he left all cases he was working on when he left the law firm in 2018 (he wrote me he left because of Klippenstein’s strong anti-LSO voluntary* Statement of Principles). Wanless did not quit the Choc v Hudbay case Klippensteins took on years after taking on mine; he took that case with him. Klippenstein even recently chased covid-denying law-breaker Adam Skelly.

The prejudice against me, the public interest, and my lawsuit and the horrific stress caused to me by my own lawyers for 2.5 years is appalling – with no authority stepping in to assist me. Law Societies are self-regulating (lawyers regulating lawyers) like the oil and gas industry regulates itself with 100% industry-funded agencies run by oil and gas people. Canada’s judges self regulate too, via the Canadian Judicial Council. Canadian civil litigants can be abruptly abandoned, after more than a decade and nearly half a million dollars sacrificed. What is the point of legal representation when lawyers can fabricate whatever they like with which to quit cases and then misrepresent their clients to the court to transfer blame and punish like any old bully? How are Canadian civil litigants to trust their lawyer, if they can lie and quit without consequence, whenever and however they want, contrary to the “rules?” How are Canadians to trust judges when they lie in rulings, and worse, are allowed to get away with it?

Sossin’s case overview was published seven months after my lawyers quit. I stumbled upon it two years later (in March 2021).

Imagine my surprise, when I read that then Dean of Osgoode Hall Law School, Lorne Sossin (now Justice on the Court of Appeal of Ontario) included my case in his review (see Part 3 below). I was even more surprised by the heading he chose for it. Thank you Justice Sossin.![]()

Constitutional Cases 2017: An Overview by Lorne Sossin, online March 19, 2019, The Supreme Court Law Review: Osgoode’s Annual Constitutional Cases Conference Volume 88 (2019), Article 1

Part I

Introduction

This contribution reviews the Constitutional Cases issued by the Supreme Court in 2017. The analysis is divided into two parts. In the first part, I analyze the year as a whole, identifying noteworthy trends. In the second part, I explore some specific constitutional decisions of the Court — especially those concerning issues which in my view have important implications for the future of the Court and its constitutional jurisprudence.

I. 2017: A YEAR IN REVIEW

2017 might best be described as a year in transition for the Supreme Court of Canada. This year represented Chief Justice McLachlin’s last on the Court (though cases on which she participated continued to be released through June 2018). This year was also Justice Malcolm Rowe’s first on the Court. The appointment of Sheilah Martin on November 29, 2017 to fill one of the “Western Canada” seats on the Court was closely watched. While Justice Martin was widely respected as qualified for the Court, this appointment was criticized by some as a missed opportunity to appoint Canada’s first Indigenous Supreme Court Justice.1

The appointment of Justice Richard Wagner to assume the role of Canada’s new Chief Justice, underscored the transitional feel to 2017. Consequently, it was a year of reflection and taking stock of the“McLachlin Court”,2 and prognostications about what lies in store with the “Wagner Court”, as much as it included a range of important new and in some cases contentious Constitutional decisions.

As Canada’s Constitutional jurisprudence matures, the trend towards fewer bold, open-ended decisions and more pragmatic, strategic decisions appears more pronounced. This trend found expression, for example, in a cluster of cases involving Reconciliation and the development of Canada’s Constitution in the context of First Nations and Indigenous Peoples, in a cluster of cases involving criminal justice reforms and in a case involving the scope of constitutional remedies. I will discuss these clusters and other trend-setting aspects of the Constitutional Cases of 2017 below.

Significantly, in her last year on the Court, Chief Justice McLachlin authored the most majority decisions (four). Justice Karakatsanis also authored or co-authored four majority reasons in 2017, suggesting her emergence as a key centrist voice on the Court. Justices Côté and Moldaver each authored two dissenting judgments while four justices — Abella, Karakatsanis, McLachlin and Brown — authored or co-authored one dissenting judgment each. In his last set of majority reasons on the Court, Justice Thomas Cromwell (who resigned in 2016), wrote controversial majority reasons in Ernst,5 discussed below. Marking his first full year on the Court, Justice Rowe was not the sole author of a single majority or dissenting opinion (though he did co-author the majority decision in Ktunaxa Nation, and penned concurring reasons in R. v. Jones and R. v. Marakah,6 each discussed below).

Against this backdrop of transitions and crossroads for the Supreme Court of Canada, I explore some of the most notable cases of 2017.

II. 2017: THE YEAR, IN CASES

As noted above, the Supreme Court decided 19 cases featuring the Constitution. The most significant activity involved developments under sections 2 and 7 of the Charter7 and section 35(1) of the Constitution Act, 1982.8

The analysis below is divided into three sections. First, I discuss a cluster of cases exploring Indigenous rights under the Charter (Ktunaxa Nation), and under section 35 of the Constitution Act, 1982 (the companion cases of Chippewas of the Thames; Clyde River and Nacho Nyak Dun).9 Second, I examine two criminal justice cases (R. v. Cody and R. v. Marakah),10 which each speak in very different ways to efforts to modernize criminal justice in Canada. Third and finally, I offer reflections on the puzzle of constitutional remedies to which the Court’s muddled reasons in Ernst11 gives rise.

I do not mean to suggest only these 2017 constitutional cases from the Supreme Court of Canada merit attention. For many, the Court’s examination of section 7 liberty rights in a labour context in Assn. of Justice Counsel12 may well be the decision with farthest-reaching implications.13 Others will point to the significance of the interplay between section 7 rights, extradition and reasonableness review in India v. Badesha14 as one of the most noteworthy.15

While I do not claim the cases discussed below are more deserving of scrutiny, below I explore why I believe these three areas of constitutional case law in 2017 reflect important trends or dilemmas for the future.

1. Reconciliation and the Constitution

In each of the disparate Supreme Court cases involving the Constitution and Indigenous Peoples in 2017, the Court links its jurisprudence to the overarching goal of Reconciliation. For example, in the opening words of Nacho Nyak Dun,16 Karakatsanis J. stated: “As expressions of partnership between nations, modern treaties play a critical role in fostering reconciliation. Through section 35 of the Constitution Act, 1982, they have assumed a vital place in our constitutional fabric.”17

The Court reiterated a similar normative framework for the duty to consult and accommodate in Ktunaxa Nation, Chippewas of the Thames and Clyde River.18 That duty, first set out in detail in Haida Nation v. British Columbia (Minister of Forests),19 is based on the following rationale:

Put simply, Canada’s Aboriginal peoples were here when Europeans came, and were never conquered. Many bands reconciled their claims with the sovereignty of the Crown through negotiated treaties. Others, notably in British Columbia, have yet to do so. The potential rights embedded in these claims are protected by s. 35 of the Constitution Act, 1982.

The honour of the Crown requires that these rights be determined, recognized and respected. This, in turn, requires the Crown, acting honourably, to participate in processes of negotiation. While this process continues, the honour of the Crown may require it to consult and, where indicated, accommodate Aboriginal interests.

…

The jurisprudence of this Court supports the view that the duty to consult and accommodate is part of a process of fair dealing and reconciliation that begins with the assertion of sovereignty and continues beyond formal claims resolution. Reconciliation is not a final legal remedy in the usual sense. Rather, it is a process flowing from rights guaranteed by s. 35(1) of the Constitution Act, 1982. This process of reconciliation flows from the Crown’s duty of honourable dealing toward Aboriginal peoples, which arises in turn from the Crown’s assertion of sovereignty over an Aboriginal people and defacto control of land and resources that were formerly in the control of that people. As stated in Mitchell v. M.N.R., [2001] 1 S.C.R. 911, 2001 SCC 33, at para. 9, “[w]ith this assertion [sovereignty] arose an obligation to treat aboriginal peoples fairly and honourably, and to protect them from exploitation” (emphasis in original).20

While Reconciliation may well be a “process” and the result of a “partnership”, it is a conceptual framework with limits, and in 2017 the Supreme Court affirmed the nature and scope of those limits. The thread woven into the cluster of cases exploring Reconciliation in 2017 also may be seen as one of judicial restraint. The Court is prepared to referee Reconciliation procedurally, in other words, but not to intervene in order to ensure just outcomes. These cases underscore and reflect the procedural ascendancy which has come to characterize the McLachlin Court more generally.21

In Nacho Nyak Dun, mentioned above, the Court considered the implications of a modern comprehensive treaty between Yukon and First Nations. The Court characterized the case as a judicial review of a land use plan developed according to the terms of a treaty, and held that the provisions of this treaty required a more collaborative process to the management of a watershed than that engaged in by the Yukon Government.

The dispute grew out of a process to govern the Peel Watershed in Yukon. In 2004, the Peel Watershed Planning Commission was established to develop a regional land use plan for the Peel Watershed. Following an extensive process, the Commission submitted its Recommended Peel Watershed Regional Land Use Plan to Yukon and the affected First Nations. Near the end of the approval process, and after the Commission had released a Final Recommended Plan, Yukon proposed and adopted a final plan that made substantial changes to increase access to and development of the region.

Justice Karakatsanis, writing for the Court, noted that in a judicial review concerning the implementation of modern treaties, a court should focus on the legality of the impugned decision, rather than closely supervise the conduct of the parties at each stage of the treaty relationship. She observes that, “Reconciliation often demands judicial forbearance”, notwithstanding that under section 35 of the Constitution Act, 1982, modern treaties are constitutional documents, and courts must continue to perform an important role in safeguarding the rights they enshrine.

The Court held that while Yukon had the power to make minor modifications to land use plans, it did not have the authority to make the extensive changes that it made to the Final Recommended Plan for the Peel Watershed, and that the trial judge therefore appropriately quashed Yukon’s approval of its plan and returned the matter to a stage of further consultation. While Yukon was not necessarily constrained in pursuing the development projects to which the revised land use plan was directed, it had failed to act “honourably” within the requirements of section 35 of the Constitution Act, 1982 in the process it undertook to finalize this plan.

Even the procedural obligations of Canadian governments affirmed in Nacho Nyak Dun seemed uncertain in the companion cases, Chippewas of the Thames and Clyde River.22Haida and subsequent case law left open to what extent and in what contexts Canadian governments could delegate the duty to consult and accommodate to regulatory agencies, tribunals and other arm’s length executive branch entities.

In Chippewas of the Thames, the Supreme Court addressed whether the regulatory process established by the National Energy Board (NEB) in relation to the approval of a pipeline project could satisfy the duty to consult and accommodate. The NEB issued notice to Indigenous groups, including the Chippewas of the Thames First Nation, informing them of the project, the NEB’s role, and the NEB’s upcoming hearing process. The Chippewas were granted funding to participate in the process, and they filed evidence and delivered oral argument delineating their concerns that the project would increase the risk of pipeline ruptures and spills, which could adversely impact their use of the land.

he NEB eventually approved the project, and was satisfied that potentially affected Indigenous groups had received adequate information and had the opportunity to share their views. The NEB also found that potential project impacts on the rights and interests of Aboriginal groups would likely be minimal and would be appropriately mitigated. Writing for the Court, Karakatsanis and Brown JJ. held that the NEB’s process satisfied the duty to consult and accommodate. The Court found that as a statutory body with the delegated executive responsibility to make a decision that could adversely affect Aboriginal and treaty rights, the NEB acted on behalf of the Crown in approving Enbridge’s application. Consequently, the Crown, through the NEB, had an obligation to consult. The Crown, in discharging its duty, may rely on steps taken by an administrative body to fulfil its duty to consult so long as the agency possesses the statutory powers to do what the duty to consult requires in the particular circumstances. To discharge its constitutional duty in this way, it must be made clear to the affected Indigenous group that the Crown is relying on this arm’s length body’s process, as the Court found was the case in the context of the NEB and the Chippewas of the Thames.

The Court held further held that the duty to consult is not the vehicle to address historical grievances. The subject of the consultation is the impact on the claimed rights of the current decision under consideration. Even taking the strength of the Chippewas’ claim and the seriousness of the potential impact on the claimed rights at their highest, the consultation undertaken in this case was clearly “adequate” in the eyes of the Court. Potentially affected Indigenous groups were given early notice of the NEB’s hearing and were invited to participate in the process. The Chippewas accepted the invitation and appeared before the NEB. They were aware that the NEB was the final decision-maker. Moreover, they understood that no other Crown entity was involved in the process for the purposes of carrying out consultation. The Court concluded that the circumstances of this case made it sufficiently clear to the Chippewas that the NEB process was intended to constitute Crown consultation and accommodation.

In the companion case, Clyde River,23 which involved similar issues and a similar process of decision-making through the NEB, the outcome was the opposite. The proponents in Clyde River applied to the NEB to conduct offshore seismic testing for oil and gas in Nunavut. The proposed testing could negatively affect the treaty rights of the Inuit of Clyde River, who opposed the seismic testing, alleging that the duty to consult had not been fulfilled in relation to it. The NEB granted the requested authorization. It concluded that the proponents made sufficient efforts to consult with Aboriginal groups and that Aboriginal groups had an adequate opportunity to participate in the NEB’s process. The NEB also concluded that the testing was unlikely to cause significant adverse environmental effects.

Applying a similar test as Chippewas of the Thames, in this case, the Court quashed the decision of the NEB as it failed to meet the standard of adequate consultation. Once again writing for the Court, Karakatsanis and Brown JJ. found that when affected Indigenous groups have squarely raised concerns about Crown consultation with the NEB, the NEB must address those concerns in reasons. In this case, the Court found that the NEB’s inquiry was misdirected. The NEB considered environmental impact of the proposed project, but the consultative inquiry should have been on the Indigenous group’s section 35 rights themselves. Here, the NEB gave no consideration to the source of the Inuit’s treaty rights, nor to the impact of the proposed testing on those rights. Second, although the Crown relied on the processes of the NEB as fulfilling its duty to consult, that was not made clear to the Inuit. Finally, the NEB made available only limited opportunities for participation and consultation by Inuit groups (for example, there were no oral hearings and there was no participant funding, as in the Chippewas of the Thames).

While the Court’s decision in Clyde River represented a significant victory for the appellants in the case, which should not be minimized, this judgment along with the Chippewas of the Thames, arguably represents a step backwards (or at least sideways) in the journey toward Reconciliation. Emerging from the Crown’s fiduciary obligations and the Honour of the Crown, the duty to consult and accommodate was elaborated in HaidaNation (and the companion case Taku River Tlingit First Nation v. British Columbia (Project Assessment Director))24 as a hopeful initiative to ensure section 35 rights were top of mind as the Crown makes decisions affecting territories subject to Indigenous claims.25 In light of these most recent decisions, it appears that the Crown need not design processes with Indigenous rights in mind at all — rather, as long as existing statutory bodies such as the NEB have mandates to consult, and the Crown provides notice to affected Indigenous groups that consultations by the arm’s length body will constitute the Crown’s consultation, the Crown can rely on such bodies to discharge their constitutional duties, even where these bodies do no more than permit Indigenous groups to participate on similar terms to all other “stakeholders”. In other words, the duty to consult and accommodate under section 35 is fast becoming just another version of procedural fairness, and the Court seems to have retrenched from the initial position expressed by McLachlin C.J.C. in Haida Nation that “[t]he honour of the Crown cannot be delegated.”26

The aspirations of Reconciliation suffered another setback in Ktunaxa Nation.27 This decision involved a challenge to a proposed ski resort development in the traditional territories of the Ktunaxa First Nation in British Columbia (a place known as Qat’muk, which has spiritual significance as home to Grizzly Bear Spirit, a principal spirit within Ktunaxa religious beliefs and cosmology).

The Ktunaxa were consulted about this proposed development and raised concerns about the impact of the project, which led to some modifications to the proposal and additional consultations. After these further consultations, the Ktunaxa adopted the position that accommodation was impossible because the project would drive Grizzly Bear Spirit from Qat’muk and therefore irrevocably impair their religious beliefs and practices. The British Columbia Government declared that reasonable consultation had occurred and approved the project.

Writing for a majority of the Court, McLachlin C.J.C. and Rowe J. held that the Minister’s decision did not violate the Ktunaxa’s section 2(a) Charter right to freedom of religion, as their concern was an “object” of belief, not the Ktunaxa’s freedom to hold their beliefs or their freedom to manifest those beliefs. This aspect of the judgment is discussed elsewhere in this volume,28 but suffice it to say that the juxtaposition between the “freedom” to believe and the “objects” of that belief flows from an expressly non-Indigenous approach to spirituality, as opposed to an approach attempting to “reconcile” Western and Indigenous spiritual approaches or between Western and Indigenous law.

Beyond the religious freedom aspect of the decision, the Court also considered the Minister’s decision that the Crown had met its duty to consult and accommodate under section 35 of the Constitution Act, 1982. The Court noted that the Minister’s decision to approve a project for development is entitled to deference. A court reviewing an administrative decision under section 35 does not decide the constitutional issue de novoraised in isolation on a standard of correctness, and therefore does not decide the issue for itself.29 Rather, in a blend of administrative law and constitutional law standards, the court must ask whether the decision-maker’s finding on the issue (that is, that the Crown’s duty to consult and accommodate was met in these circumstances) was reasonable.

Framed in this way, the Court need only conclude that the Minister’s determination that the consultation and accommodation was adequate represented one of the possible findings which could be made in these circumstances, not that it was the correct or appropriate finding. The Court further noted that Aboriginal rights must be proven by “tested evidence”; they cannot be established as an incident of administrative law proceedings that centre on the adequacy of consultation and accommodation. In other words, the subject matter of this was whether the consultations were adequate, not whether the impact on the affected Indigenous community justified objecting to the project. For McLachlin C.J.C. and Rowe J., “consultation and accommodation” will not resolve underlying claims, but rather constitute the best available legal tool. They observe:

The Ktunaxa reply that they must have relief now, for if development proceeds Grizzly Bear Spirit will flee Qat’muk long before they are able to prove their claim or establish it under the B.C. treaty process. We are not insensible to this point. But the solution is not for courts to make far-reaching constitutional declarations in the course of judicial review proceedings incidental to, and ill-equipped to determine, Aboriginal rights and title claims. Injunctive relief to delay the project may be available. Otherwise, the best that can be achieved in the uncertain interim while claims are resolved is to follow a fair and respectful process and work in good faith toward reconciliation. Claims should be identified early in the process and defined as clearly as possible. In most cases, this will lead to agreement and reconciliation. Where it does not, mitigating potential adverse impacts on the asserted right ultimately requires resolving questions about the existence and scope of unsettled claims as expeditiously as possible. For the Ktunaxa, this may seem unsatisfactory, indeed tragic. But in the difficult period between claim assertion and claim resolution, consultation and accommodation, imperfect as they may be, are the best available legal tools in the reconciliation basket.30

Thus framed, the Court held that the record in Ktunaxa Nation supported the reasonableness of the Minister’s conclusion that the section 35 obligation of consultation and accommodation had been met.

KtunaxaNation reveals the limits of a framework of consultation and accommodation. Ultimately, where a First Nation or Indigenous community is simply opposed to a project, as here, the framework tends to favour the Crown as long as it demonstrates that it appreciates the objections and makes some modifications to the project in light of the objection. The Court concluded in this context, for example, that while the Minister did not offer the ultimate accommodation demanded by the Ktunaxa — complete rejection of the ski resort project — the Crown met its obligation to consult and accommodate by modifying the proposal. As the Court expressly notes, section 35 guarantees a process, not a particular result or a veto, and that where adequate consultation has occurred, a development may proceed without consent. The dissonance between the duty to consult and accommodate framework as articulated in Ktunaxa Nation and the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (“UNDRIP”),31 and its emphasis on “free, prior and informed” consent by Indigenous Peoples with respect to use of their territory, is striking.

The increasingly procedural approach to section 35 in the cases discussed above, also shows the conceptual and practical limits of the Court’s embrace of Reconciliation. In the view of the Supreme Court, the goal of Reconciliation remains how to address “Aboriginal rights” in the context of Canadian law and Crown sovereignty. In the eyes of many First Nations and Indigenous Peoples, however, Reconciliation must in the end address Indigenous laws and sovereignty as well. It remains unclear whether the section 35 jurisprudence of the Supreme Court (or whether the Supreme Court as an institution itself rooted in Canadian claims to sovereignty) is up to the challenge of Reconciliation conceived in this way.32

Just as the Court has confronted the crossroads of Reconciliation, it also found itself grappling with transformational change in the criminal justice system as well. It is to that sphere that my analysis now turns.

2. Criminal Justice Reform and Frameworks for the Future

…

3. Statutory Bars to Constitutional Remedies: The Importance of Being Ernst

In Ernst,45 the Supreme Court of Canada considered the availability of Charter damages in the face of a statutory bar to civil litigation against a public regulator. In this third area of focus among the constitutional cases of 2017, I consider the Court’s rationale in Ernst for upholding this statutory bar and the implications of the Court’s analysis for a coherent relationship between statutory and constitutional interpretation in Canada.46

The case arose in the context of a property owner, Jessica Ernst, who was seeking various remedies against private and public parties she believed to be responsible for harm to her property as a result of fracking activities. One of the defendants in her claim was the Alberta Energy Regulator (“AER”), a statutory, quasi-independent energy regulator. Among other grounds for relief, Ernst alleged she was “punished” by the AER for publicly criticizing it and that she was prevented by the AER from speaking out for a period of 16 months. Ernst claimed that her section 2(b) Charter right to freedom of expression was breached, and that Charter damages should be available to remedy that breach. As this case arises from a motion to strike her claim based on pleadings, all the facts alleged by Ernst had to be accepted by the court as true.

Section 43 of the Energy Resources Conservation Act (the “Act”),47the statute that governs the AER, immunizes it from civil claims for actions it takes pursuant to its statutory authority. Both the Alberta Court of Queen’s Bench and the Alberta Court of Appeal found that the immunity clause on its face bars Ernst’s claim for Charter damages and concluded therefore that her claim against the Board should be struck out. On appeal to the Supreme Court of Canada, for the first time, she added to her claim a challenge to the constitutional validity of section 43 of the Act. The immunity clause at issue reads:

No action or proceeding may be brought against the Board or a member of the Board or a person referred to in section 10 or 17(1) in respect of any act or thing done purportedly in pursuance of this Act, or any Act that the Board administers, the regulations under any of those Acts or a decision, order or direction of the Board.48

The majority judgment (authored by Cromwell J. in one of his final judgments), concludes that since Ernst herself acknowledged the statutory bar precluded her claim for Charter damages (and therefore should be struck down), and no authorities were offered in support of the view that the statutory bar did not preclude that claim, then the Supreme Court of Canada had to proceed on that basis. Justice Cromwell separately concluded that even if a Charter damages claim were permitted, however, such a claim would fail in these circumstances because of the countervailing factors against the awarding of Charter damages as recognized in Vancouver (City) v. Ward.49

In Ward, the Court set out a framework for the Charter damages claims under section 24(1), under which the claimant must demonstrate that her or his Charter rights had been breached and that damages would serve as compensation, vindication, or deterrence. Once that burden is met, the state has the onus to demonstrate that damages should not be awarded based on countervailing considerations (such as the availability of alternative remedies and good governance arguments).

The majority’s view that it must accept the statutory bar precluding a claim to Charter damages because the claimant seems to accept this premise unduly fetters the discretion of the Court. If the proper understanding of a Charter doctrine has not been advanced by the parties, this does not mean the Court must accept an improper understanding, as the Court itself has acknowledged in the past.50 It is always open to the Court to reach a conclusion on a question of constitutional interpretation even if it differs from the position advanced by the parties or where the parties have chosen for their own reasons not to advance that argument.

For reasons set out below, in my view, the premise the Supreme Court of Canada accepts in Ernst, that a statutory immunity clause can in any circumstances bar a Charter claim, is suspect. The majority’s discussion of countervailing factors is also unpersuasive. The existence of countervailing factors, as set out above, only arises where a party’s entitlement to Charter damages has been established and where the Crown seeks to demonstrate that damages nonetheless should not be awarded.

First, a preliminary motion to strike Ernst’s claim against the AER because of the statutory bar to Charter damages should not depend on whether she has a strong or weak case to actually establish her entitlement to damages, nor on whether the Crown has or does not have grounds to raise countervailing factors.

In other words, either her Charter claim is barred (in which case the analysis of countervailing factors is irrelevant), or it is not barred (in which case the analysis of countervailing factors is premature).

Second, the existence of countervailing factors in this case is not compelling. The majority asserts that because judicial review is available on administrative law grounds, this alternative remedy militates against the availability of Charter damages. The effect of the majority finding is that while a common law remedy (judicial review) cannot be barred by statute, a constitutional remedy (Charter damages) can be. This finding is puzzling. Statutes always must be interpreted in ways that safeguard, not inhibit, the protection of Charter rights and freedoms.

The countervailing good governance concerns also fall flat. Justice Cromwell notes that the Board must be free from the anxiety of constant litigation in pursuing its statutory goals. While this might be relevant where a claim relates to someone aggrieved by the regulatory actions of a regulator, Ernst involves a regulator engaging in alleged punitive behaviour in an attempt to silence a complainant. A suit for Charter damages is not the same as a suit for civil damages, and the Supreme Court of Canada’s desire to frame the former as a species of the latter (rather than as part of the spectrum of remedies for Charter breaches per se) leads the majority of the Court, in my view, down a problematic path.

In reaching this conclusion, the majority relies on cases involving the high bar for negligence claims against public regulators — Cromwell J. observes, “[w]hile, as noted, Charter damages are an autonomous remedy, and every state actor has an obligation to be Charter-compliant, the same policy considerations as are present in the law of negligence nonetheless weigh heavily here ….”51

The second point in this passage simply does not follow from the first. If Charter damages represent an autonomous remedy, and if every state actor has an obligation to be Charter-compliant, then the case law relating to negligence against state agencies sheds little if any light on the issue (just as the majority of the Supreme Court of Canada, in Henry v. British Columbia (Attorney General),52 held that the tort of malicious prosecution did not shed light on the test appropriate for Charter damages claims against Crown prosecutors). The search for remedies that are “just and appropriate” under section 24 of the Charter is fundamentally distinct from the search for a duty of care and breach under the common law tort of negligence.

The dissenting group of four justices, led by McLachlin C.J.C. and Moldaver and Brown JJ. (Côté J. concurring), conclude that Ernst’s claim should not be struck, as it was not plain and obvious that Charter damages could in no circumstances be an appropriate and just remedy in a claim against the Board. Further, they concluded it is not plain and obvious that Ernst’s claim is barred by section 43. The dissenting justices come to a more sound conclusion, but their reasoning is also based on a faulty premise. They stated:

In deciding whether a claim for Charter damages should be struck out on the basis of a statutory immunity clause, the court must first determine whether it is plain and obvious that Charter damages could not be an appropriate and just remedy in the circumstances of the plaintiff’s claim.53

By suggesting that the merits of the Charter damages have to be assessed before considering the scope of the statutory immunity clause, the dissenting justices, like the majority, seem to put the statutory cart before the constitutional horse. It is entirely possible that Charter damages are not warranted in the circumstances of this case (though it is uncertain on what grounds the Court could reach such a determination while also accepting all the facts as pleaded by the claimant as true), but that analysis has little to do with whether a statutory bar can preclude a section 24 Charter remedy. The issue in the appeal to the Supreme Court of Canada was the scope of the statutory immunity clause, not the strength of the claim to Charter damages.

In my view, the answer to the question regarding the statutory immunity clause raised in this case is far simpler than the approach taken by the majority or dissenting justices. An immunity clause can preclude only those claims that a legislature has the constitutional authority to bar — that includes civil claims for damages, but it cannot bar Charter claims (including Charter claims, as in Ernst, where one of the remedies sought is Charter damages). On this reading, the Supreme Court of Canada could and should have interpreted the statutory bar as inapplicable to this claim to the extent a breach of the Charter is properly pleaded. Further, to Abella J.’s objection in her concurring reasons, the Alberta Government would not need to have received formal notice of the claim, since the validity of the statutory immunity clause does not arise as a live issue if it is interpreted as inapplicable to Charter claims.

Returning to my broader objection with the majority of the Supreme Court of Canada’s approach to Charter damages, the claim in this case, on its face, is that a Charter breach has occurred. Ernst claims she was silenced as punishment for her opposition to the Board.

The availability of Charter damages, like the availability of other Charter remedies (declarations, injunctions, etc.), cannot be precluded by an act either of a provincial legislature or of Parliament (unless the notwithstanding clause under section 33 is invoked, which is the sole mechanism for immunizing public bodies from Charter scrutiny, and therefore, from Charter remedies). Legislation can limit the availability of Charter remedies from administrative tribunals and regulators as they have no inherent powers, and so can only provide those constitutional remedies which fall within their statutory jurisdiction,54 but here, the remedy sought is from a court.

In my view, the Court in Ernst misconstrues the place of Charter damages in the context of Canada’s constitutional architecture. It is important to recall what is at issue in Ernst. The case is not about whether the Charter was breached, or, if so, whether Charter damages are appropriate — rather, this case is about whether a claimant should have a chance to prove her allegations of a Charter breach warranting damages as a remedy, and whether a statute can bar her from having such an opportunity. By upholding the validity of a statute to bar a Charter remedy, the Supreme Court of Canada has allowed a legislature to unilaterally circumscribe constitutional protections and done so for no broader constitutional rationales or benefits.

III. CONCLUSION

The constitutional cases of 2017 may well be overshadowed by the significant transitions which occurred during this eventful year, and in particular, the retirement of Chief Justice McLachlin. She will, I think, be remembered for her remarkable energy and productivity, her gift for consensus-building on the Court, her courage in the face of the criticism from Prime Minister Harper in 2014 as part of the fallout from the invalidated appointment of Justice Marc Nadon, and her growing commitment, particularly as Chief Justice, to the field of Reconciliation with First Nation and Indigenous Peoples.

That said, the Supreme Court’s constitutional cases of 2017 merit scrutiny for several reasons. As set out in the analysis above, I believe this year will be seen as a setback in the journey toward Reconciliation, on the basis of Chippewas of the Thames, Clyde River and Ktunaxa Nation. I believe this year highlights the tensions in the Court’s role in criminal justice reform between adapting existing frameworks to meet future challenges, such as the digital transformation touched upon in Marakah, or developing new frameworks, such the Jordan framework, applied to the administrative and advocacy hurdles to reduce delay in Cody. Finally, I believe Ernst will be remembered as a problematic precedent in working out the relationship between statutory interpretation on the one hand, and the requirements of the Constitution on the other.

For all of these reasons, in the context of the Supreme Court of Canada and the Constitution, 2017 was a year to remember!

Refer also to:

Slides above from Ernst speaking presentations

In 2013, I ended many of my public talks with the above slide of Frac’d Lady Justice and posted it to my website. Cory Wanless and Murray Klippenstein did not quit then.

They also did not quit in 2015 when Andrew Nikiforuk’s Slick Water was published. I bought copies and mailed them to Wanless and Klippenstein and a few others at the firm, thanking them. They gave the book two thumbs up and made no complaints about the last paragraph, during editing (which they were part of) or after the book was published.

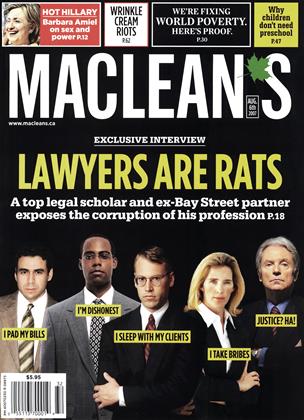

… The whole question of the values behind the rules of the legal system is not on the whole of great interest to law schools or the legal profession. And there’s an additional point: lawyers are taught to manipulate the rules….

If you’re taught how to manipulate rules, you lose respect for them, and that leads to a kind of arrogance: I’m bigger than the rules, I’m not the average man on the street who needs to be law-abiding because I know how to get around the rules. And there may be just a touch of the more common form of arrogance, too, which is “I’m smarter than they are, they’ll never catch me.”

… The disciplinary process of the law societies in this country is deeply flawed.

… I think Canada really has to get its act together. Look at the reforms in the U.K., which woke up some years ago to this problem and [adopted] quite sweeping reforms that largely removed self-regulation from the legal profession. Why in heaven the same sort of reforms are not under consideration in this country I do not know, except that self-regulation is regarded with quasi-religious fervour. …

***

*Voluntary because lawyers did not have to disclose their statement to anyone, not even the LSO, so who would have known if they completed one or not. The SOP was scantily enforced, if at all, with no punishment if not completed, certainly no jail time or murder by racist police.